The Problematic Paradox of Carbon Offsets

The world is facing a combined climate and biodiversity crises. Carbon offsets are promoted as a solution to both - but there is mounting evidence that they could just be making things worse.

In the early weeks of 2023, I had the very fortunate opportunity to travel to a very hot and humid Malaysia.

Malaysia is one of the world’s megadiverse countries. These are countries that are host to large numbers of unique species of animals, plants and insects. It is a status that Malaysia holds primarily due to its territory extending into the rainforest-covered island of Borneo.

Borneo and many forest-dense regions across Southeast Asia are ground-zero in the raging debate about carbon offsets. It is a debate that has surged to new levels of intensity in recent months, with fresh doubts raised around the environmental benefits of carbon offsets and the growing role they play in the climate plans of major fossil fuel producers.

The world is facing two runaway environmental crises: the climate crisis - where the ongoing use of fossil fuels is slowly cooking our planet - and the biodiversity crisis - where our ongoing encroachment into nature (and the warming of our planet) is leading to unprecedented species loss.

These two crises are deeply interrelated, each exacerbating the other. Both crises are driven by human activity. The cause and remedies of both crises are also well understood, but yet we have done little to mobilise into action.

Money speaks

The UNEP has estimated that as much as US$536 billion will need to be spent annually by 2050 to adequately address the combined impacts that the climate, biodiversity, and land degradation crises are having on nature.

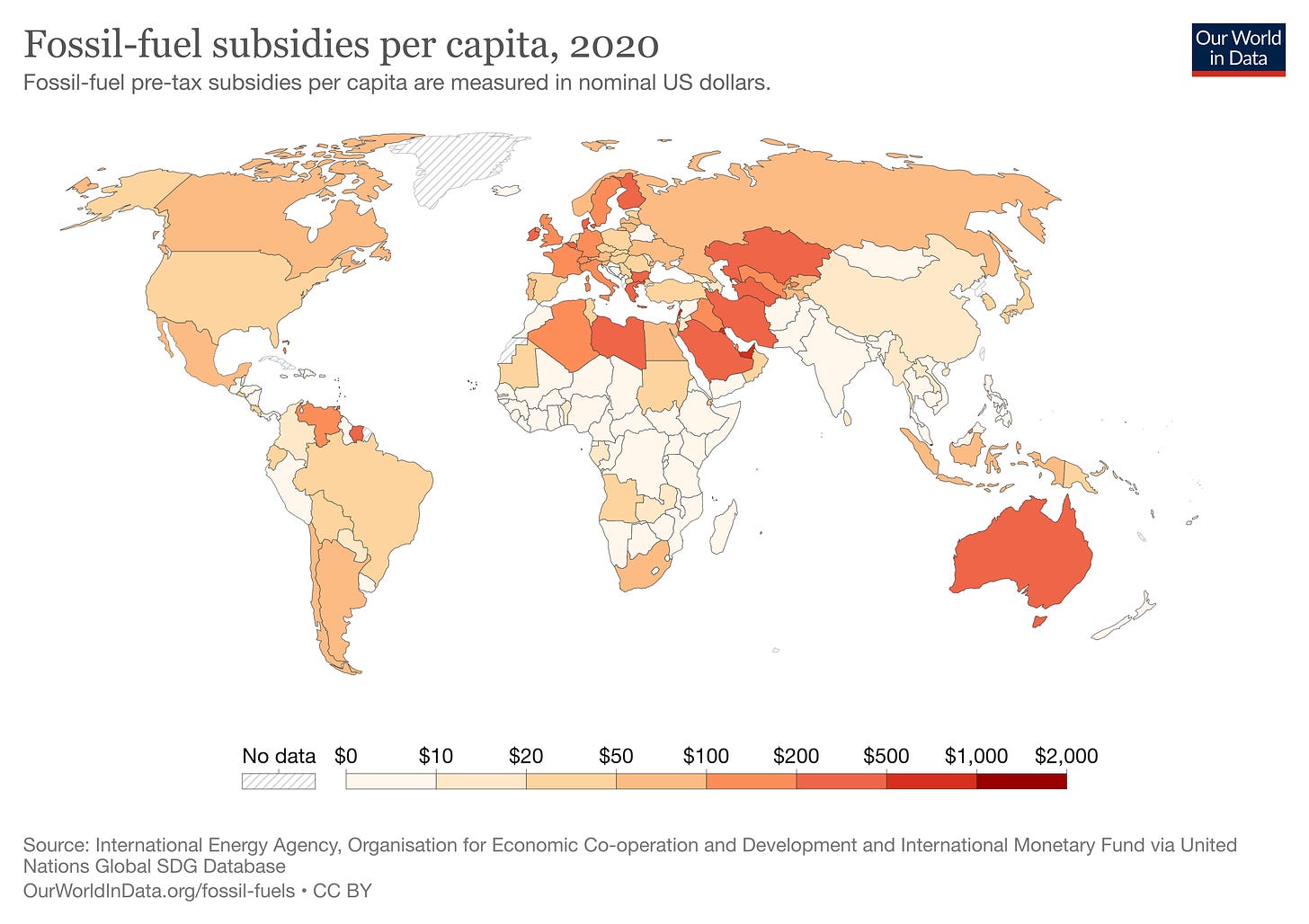

It sounds like a lot of money, but it is less than the almost US$700 billion the world still spends subsidising the use of fossil fuels.

Money plays a big role in both crises.

The loss of the world’s forests has been at the centre of the biodiversity crisis with ancient forests, which have long served as sinks for carbon, being flattened to make way for agricultural crops like rubber, soy and palm oil.

As we currently lack ways to financially incentivise the conservation of forests and preserve their biodiversity - we don’t have mechanisms to put a financial value on biodiversity - the potential revenues from the agricultural crops too frequently overwhelm efforts to protect forests.

This is where the push for carbon offsets comes in.

Advocates for nature-based carbon offset markets argue they can help fill the finance gap.

It is argued that by linking the creation of offsets to the preservation of forests, it could be possible to ‘mobilise’ public sector investment into the protection of forests, helping to mitigate the pressures to clear forests to make way for money crops.

Revenues from offsets could provide the financial impetuous to protect the forests that serve as habitat for some of the world’s most threaten species, such as the orangutans, leopards, elephants and rhinos that have called Borneo home, and maintain their status as carbon sinks.

This is all good in theory, and it sounds like a win-win.

But there is growing evidence that the claimed climate and biodiversity benefits of carbon offsets are not materialising in practice.

The problem with carbon offsets

There have long been doubts about the ‘additionality’ of nature-based carbon offsets - offsets are being awarded to projects that have not led to the protection of forests in peril. It has been found that some offsets have been awarded to projects where clearing may have continued regardless.

New peer-reviewed analysis published by The Guardian found that as much as 90 per cent of the carbon offsets issued by international accreditation group Verra to rainforest projects may have little to no environmental benefit.

The problem has been the demonstrated flaws in these methodologies. For example, the ‘reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation’ methodology – an approach commonly known by the acronym REDD which awards offset credits when trees are left standing rather than being cut down – is often based on pure hypotheticals.

Proponents claim that a particular volume of emissions is avoided by deciding not to cut down trees. But what if the trees weren’t going to be cut down in the first place? The Guardian’s analysis found that many offset projects vastly overestimated the emissions avoided because forests were not actually under threat of clearing.

Simply ‘avoiding’ emissions does nothing to reduce the overall concentration of greenhouse gas emissions in the atmosphere, particularly if the resulting credits are used to ‘offset’ emissions elsewhere in the economy. If they offset the use of coal-fired electricity or the burning of petrol in your car - the overall volume of emissions may have increased.

If you’ve ever opted into the purchase of offsets for the goods and services you buy - such as for flights or your energy use - the offsets purchased on your behalf have more than likely been issued under a voluntary offset scheme like those run by Verra or Gold Standard.

Verra rejected The Guardian’s claims, saying in a statement that ‘to ensure that this work is credible and reflects scientific consensus, Verra works with academics and experts globally to create and refine methodologies.’

Offsets are increasingly a licence for fossil fuel expansion

Despite the concerns about integrity, the voluntary offset schemes are attracting surging interest from major polluters. The market for carbon offsets is projected could be worth as much as US$40 billion a year by the end of the decade.

Buyers of these credits include major brands like Disney, BHP, Gucci, Netflix and a growing number of fossil fuel producers, who see the credits as a cheap path to ‘carbon neutrality’.

But often they are being used to mask failures to address their underlying emissions.

For example, oil and gas giant Shell committed to invest US$450 million in nature-based carbon offsets projects. It sounds like a big win for nature.

While that also sounds like a considerable amount of money, it is dwarfed by the $1.4 billion Shell reported spending in 2021 alone exploring new oil and gas reserves.

It is also just a slice of the US$485 billion expected to be spent by fossil fuel companies globally on the development of new oil and gas supplies.

Companies like Shell, who are launching themselves into the global carbon offsets market, say they understand the emissions reduction ‘hierarchy’ - long-term emissions reductions come first, and offsets account for the rest.

But in practice, these fossil fuel companies aren’t making those fundamental changes to their businesses needed to decarbonise.

This is the tragedy of the carbon offset market; one of the few ideas we have for mobilising private sector investment into nature is - in many instances - having little to no actual benefit for biodiversity and could also be working to exacerbate the climate crisis by facilitating the ongoing consumption of fossil fuels.

We have ourselves a paradox; the carbon offsets being created as means of neutralising our emissions are merely serving as a licence to increase emissions elsewhere.

The world’s emitters need to actually adhere to the carbon mitigation hierarchy they claim to be committed to. Emissions need to be reduced at their source as a priority – the conversation about offsets can be had after we’ve exhausted our efforts to cut the production of new greenhouse gas emissions.

Governments need to step in to fill the finance gap for nature.

As a good start, governments could begin by redirecting the billions in subsidies they currently provide to the fossil fuel industry towards the protection and conservation of the world’s forests.

If you’ve read this far - thank you.

This is my first post from this Substack. It is a bit of an experiment and will be an outlet for my writing and analysis throughout 2023. Thank you for your support already, and I plan to send out new additions every fortnight.

You can share this post with others by clicking the button below.